Context:

Forensic Architecture is a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London (UK). Working with activists and civil society groups, they investigate human and environmental rights violations committed by state and corporate bodies. Forensic Architecture’s work is rooted in architectural research and practice. This group of architects, researchers and technologists, gather data points about a violent event from a range of accessible sources – such as satellite imagery, witness testimony, atmospheric sensors, and cameraphone footage. They cross-reference and re-compose these into a timeline of what happened and when. This practice of ‘counter-forensics’ takes place outside the state or corporation and beyond their sources. Forensic Architecture have provided evidence to national and international courts as part of legal cases and investigations, and their work is also regularly exhibited in art galleries and other cultural institutions.

Connections to eco-social sustainability:

The Centre for Contemporary Nature is a sub-group of Forensic Architecture that focusses on the environment. Conflicts are not simply human; plants, animals and ecosystems can also be destroyed by states or corporations. In some cases, the extraction of natural resources is a major trigger for armed conflict, resulting in harm to people and ecosystems. In other cases, environmental destruction is a side effect of war.

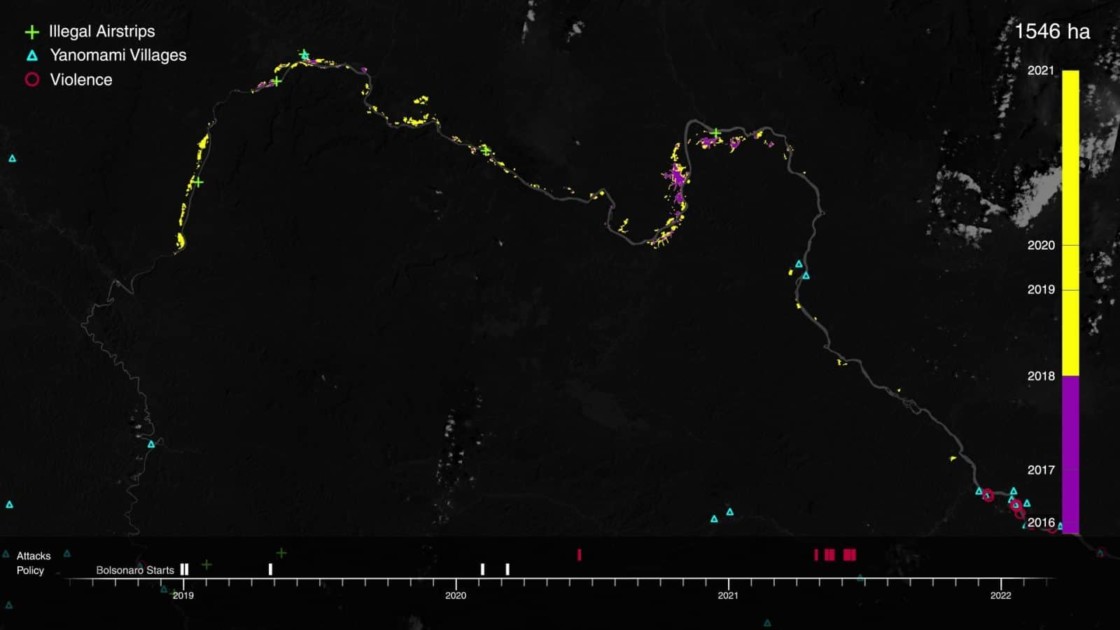

Forensic Architecture’s spatial practice often demonstrates the interconnectedness between ‘ecological’ and ‘social’ forms of violence, for example in their investigation of gold mining in the Amazon rainforest (2019-present), which links the destruction of the rainforest and its ecosystems with attacks on the Yanomami people and specific policies of the Bolsonaro administration.

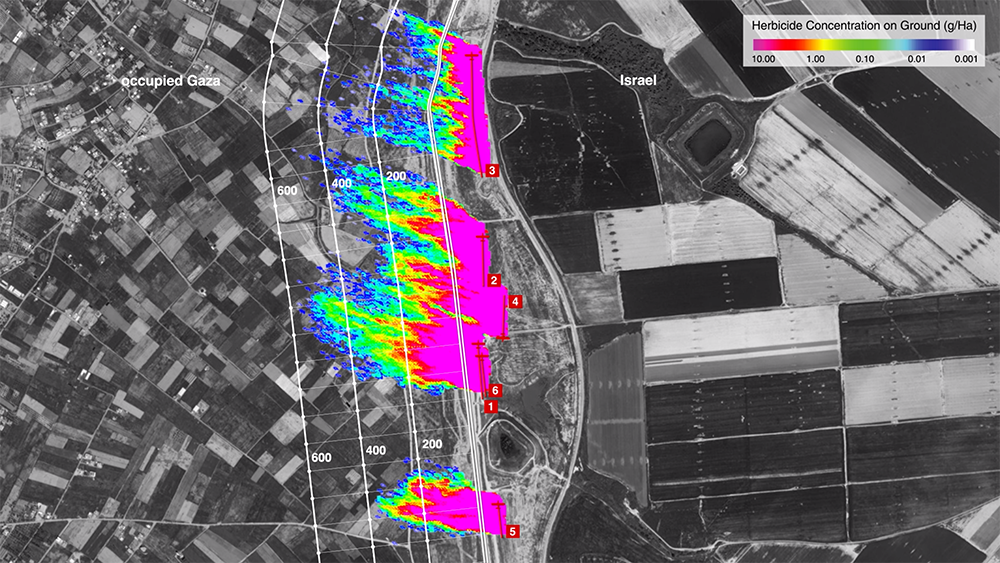

Forensic Architecture’s ongoing work in Gaza (including with Palestinian collaborators Al-Haq) shows a similar pattern, where herbicide spraying and targeted attacks on chemical factories create toxic environmental events whose impacts can last for generations.

Transformative creative practice:

Forensic Architecture incorporate tools and techniques from art and design into their investigations, and art institutions are also an important outlet for their work. In 2018, they were nominated for the Turner Prize in art.

Forensic Architecture’s founder Eyal Weizman explains “we don’t want to be limited as a technical service to the judicial system, we want it to do political work, we believe that evidence is only as good as the political process that can use it. Showing the evidence in galleries can allow for different forms of engagement, and levels of reflection” (UNSW talk, May 2022).

Since institutions each have their own boundaries, one strategy used by Forensic Architecture is to show their work in different settings.

“No forum is ever neutral, no institution in our society is a kind of perfect arena to present material in. What you can do is to offset the limitations of one by taking your evidence from the court to the media, to the art space to academic environments also” Eyal Weizman, UNSW talk, May 2022.

In a recent book called Forensic Aesthetics, media theorist Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman also use counter-forensics to contribute to art and media theory. They suggest that aesthetics should be refigured in terms of sensing and sense-making – a capacity that all kinds of material artefacts, from networked sensors and AI to clay bricks have. The gallery is not a privileged space per se, but is a somewhere that we slow down and pay attention to aesthetic connections.

“Think of galleries or courts as kind of media systems… in a gallery you slow down your movement, you attend to the detail, you look at the very specific kinds of objects that brought together in certain kinds of ways” – Matthew Fuller, interview Pierre d’Alancaisez, February 2022.

Learning and evaluation:

Since the organisation was founded in 2010, Forensic Architecture have embraced rapid technological changes, notably the increasing availability of satellite mapping data, new 3D modelling tools, user-generated content, and Artificial Intelligence systems.

“We take projects only inasmuch as we can develop new techniques… We never take projects that we know how to do. So, it requires you to constantly innovate in order to momentarily be above what you think the forces here… can do with the evidence” – Eyal Weizman, UNSW talk, May 2022.

Working to investigate well-resourced state and corporate actors, means engaging in constant innovation and learning in order to be able to counter their techniques.

Learn more:

Forensic Architecture’s website

Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman’s interview with Pierre d’Alancaisez.

Eyal Weizman’s talk at UNSW.